Modalities for radiologic evaluation of children with suspected skull fractures include: Imaging establishes the diagnosis of a skull fracture. Altered mental status after a head injury.Cranial nerve deficits leading to facial paralysis, anosmia, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, nystagmus, tinnitus, or hearing loss.Cerebrospinal fluid leak from the nose (CSF rhinorrhea).

Cerebrospinal fluid leak from the ear (CSF otorrhea).Subcutaneous bleeding over the mastoid process (Battle sign) ( picture 3).Subcutaneous bleeding around the orbit (raccoon eyes) ( picture 2).Blood behind the tympanic membrane (hemotympanum) ( picture 1).Localized tenderness and swelling of the skull or scalp, especially if associated with a palpable fracture or bony step off, skull defect, or crepitus.ĭIAGNOSIS AND RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION - Skull fractures should be suspected in patients with the following findings: However, they may go undetected for years and present with delayed onset of neurologic symptoms (headache, seizure, or neurologic deficit). They usually are detected within one year of an acute head injury as a localized swelling or palpable skull defect that increases in size. Growing skull fractures occur predominantly in children who are younger than three years of age and in whom the diastasis is greater than 3 to 4 mm. In one study of 592 children with head injuries, the prevalence was 1.2 percent.

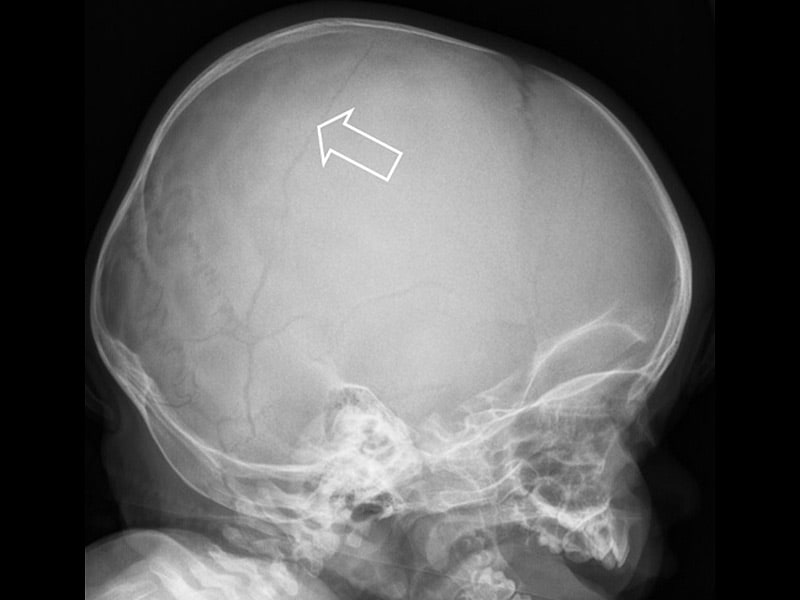

The incidence of growing fractures is not known. Neurologic findings or cranial growth asymmetry may be present if associated compression of the underlying brain is present. These fractures commonly are called growing skull fractures, traumatic encephaloceles, or leptomeningeal cysts. Enlargement is caused by herniated brain, a leptomeningeal cyst, or dilated ventricles. Growing skull fracture - Skull fractures associated with an underlying dural tear may fail to heal properly. (See "Cranial cerebrospinal fluid leaks".) The diagnosis and management of cranial cerebrospinal fluid leaks are discussed separately. Confirmation and localization of the fistula requires neuroimaging.

The parietal bone is involved most frequently, followed by the occipital, frontal, and temporal bones. The incidence of skull fractures in children who present for outpatient evaluation of head trauma ranges from 2 to 20 percent.

(See "Severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in children: Initial evaluation and management" and "Child abuse: Evaluation and diagnosis of abusive head trauma in infants and children", section on 'Skeletal evaluation'.)ĮPIDEMIOLOGY - Skull fractures result from direct impact to the calvarium and are important because of their association with intracranial injury, the leading cause of traumatic death in childhood. The approach to severe traumatic brain injury in children and skull fractures in children with inflicted injury is discussed separately. INTRODUCTION - The clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management of skull fractures in children are reviewed here.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)